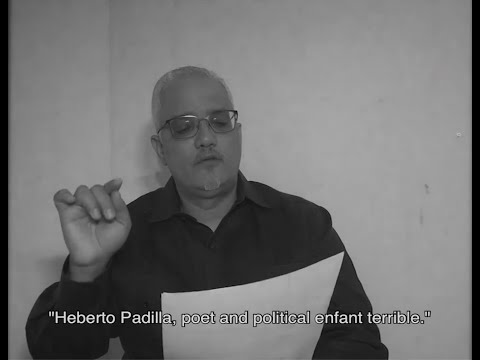

Fifty years ago, the Cuban revolution’s most celebrated poet, Heberto Padilla, emerged from the headquarters of state security, known as Villa Marista, after 36 days of interrogations and psychological torture. Two days after his release, on April 27, 1971, he was paraded before his colleagues at the Artists and Writers Union, where he uttered a two-hour auto-da-fé in which he denounced himself, his wife, and his friends as counterrevolutionaries.

Padilla’s public confession shocked the international literary world. Although the Cuban government sought to use his ritualized penance as proof of his guilt, his friends outside the island understood the event to be a Stalinist-style show trial. Prominent public intellectuals such as Susan Sontag, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Italo Calvino spoke out in his defense, and dozens of more literary figures signed public letters to Fidel Castro. Many chose to distance themselves from the revolution due to the affair, bringing Cuba’s golden age as a favored destination for globe-trotting left-wing intellectuals to a close. The tragic dimension of the poet’s confession was compounded by the fact that Padilla subsequently endured nine years of internal exile before being allowed to emigrate to the United States, where he died a broken man in 2000.

So why return to this dark moment in Cuba’s revolutionary past? Today, I will present a video performance as a commemorative act in honor of Padilla’s confession. I invited 20 Cuban artists and writers from the island and the diaspora to engage in a choral reading of the transcript of what was uttered that night, which, in addition to Padilla’s speech, includes pronouncements from cultural apparatchiks; mea culpas from the poet’s wife and close friends; one self-aggrandizing foe’s self-defense; and the comments of a befuddled fellow traveler who was exiled on the island at the time. The island-based Cubans used encrypted messaging to send me their recorded contributions to ensure that there would be no unwanted interference in their participation.

Not even the most brilliant dramatist could have imagined anything quite as pathetic as the confessions by Padilla and his cohort. As I read the words of one writer after another, straining to find ways to condemn themselves, I found myself comparing what I was reading to the absurdist plays of Eugene Ionesco. The experience for all those involved in the revival of that history has been painful and revelatory. We all knew about Padilla, but few of us had studied the words he spoke on that fateful night.

Some of the readers have told me that reading the text aloud made them feel ill or anxious or even gave them nightmares. Others delivered their parts with an obvious note of perplexity, as if they simply could not accept that such self-incriminating statements over baseless accusations would ever have been made with sincerity. And yet, deep down, all of us working on this venture recognize ourselves in Padilla’s situation.

I wanted to bring the transcripts back to life because the living conditions for artists and intellectuals in Cuba have not changed, even though the Cuban government has engaged in a massive effort over the years to obscure that truth. Outside of Cuba, few remember Padilla, what happened to him, or how his show trial affected the country’s public image. The government’s campaign to present itself as a benevolent force and the only underdog to have succeeded in challenging the United States still charms many. People who have not lived in an authoritarian society often have a hard time believing that the same government that champions free education and stages impressive cultural spectacles for tourists also imposes draconian restrictions on independent creative endeavors, criminalizes dissent, and subjects its critics to social death. But that is the case here. Cuban state security continues to survey, threaten, and detain artists and writers. Party loyalists continue to denounce artists and scholars that enjoy success abroad as conceited and suspect. And government officials persist in characterizing artists and intellectuals who are critical of the system as lackeys paid by foreign governments to foment discord and thus bring down the regime.

A Cuban who learned of the project through social media commented that:

Thanks to this document, the shadow of our fear, so jealously guarded in the closet of our collective unconscious, will no longer be something hidden. It is for the same reason that we often still speak in a low voice, or in a figurative sense, or with far-fetched extraverbal metaphors.

I also decided to revisit the confession to take note of an important cultural shift. Unlike the artists and writers that did not dare to challenge Padilla’s detention in 1971, artists and independent journalists in today’s Cuba are contesting state-orchestrated harassment of their peers and documenting the indecorous actions and words of government officials. Scores of prominent artists and writers are locked in a battle with the government over their right to express critical views. They respond to the government’s longstanding strategy of isolating opponents by forming independent organizations such as the San Isidro Movement and 27N. Although official media and cultural institutions in Cuba exclude independent creators and public protests are still banned, increased internet access in recent years has provided a platform for the airing of critical views and the circulation of “unauthorized music,” art, film, and journalism. The power and diversity of Cuban culture in the digital sphere are drowning out the monotony of state media, which does not attract young Cubans anymore.

Alarmed by the loss of its hegemony in the cultural domain, the state frantically decries its competitors as demonic enemies. Just as the Cuban government once cast foreign publishers as villains seeking to undermine the revolution by luring writers into producing works that would satisfy a foreign demand for rebellious voices, now it is the internet that is described as promoting subversion. Likewise, all forms of critique are deemed to be part of an American-controlled plot. This time, however, Cuban artists are refuting the government’s hyperbolic claims.

Artists and intellectuals in today’s Cuba are refusing to issue false confessions. They refuse to call themselves counterrevolutionaries, no matter what accusations their government levies against them. They have inherited a system that they had no part in choosing, one that has proclaimed itself to be unchangeable. They simply don’t accept that inflexibility. In a manifesto recently issued by 27N, the group demanded “that all persons who have been tried and condemned for expressing ideas contrary to the current political system be released.” They want to live in a country where Padilla would be free if he were still alive — a country where they would no longer have to live in his shadow. To get there, we all must take a moment to remember how this all began.

Padilla’s Shadow is permanently available on YouTube and Vimeo, starting at midnight on April 27, 2021. A project description can be found here, and you can read about the project via Artists at Risk Connection, Index on Censorship, the Pérez Art Museum Miami, Franklin Furnace, the Showroom, Künstlerhaus Bethanien, and Rialta.